ERLAND EDBERG

Turkey’s newly re-elected president Recep Tayyip Erdogan is using culture as a weapon to implement his neo-Ottoman vision for the country. While nationalists are rejoicing, there is no place for oppositional voices.

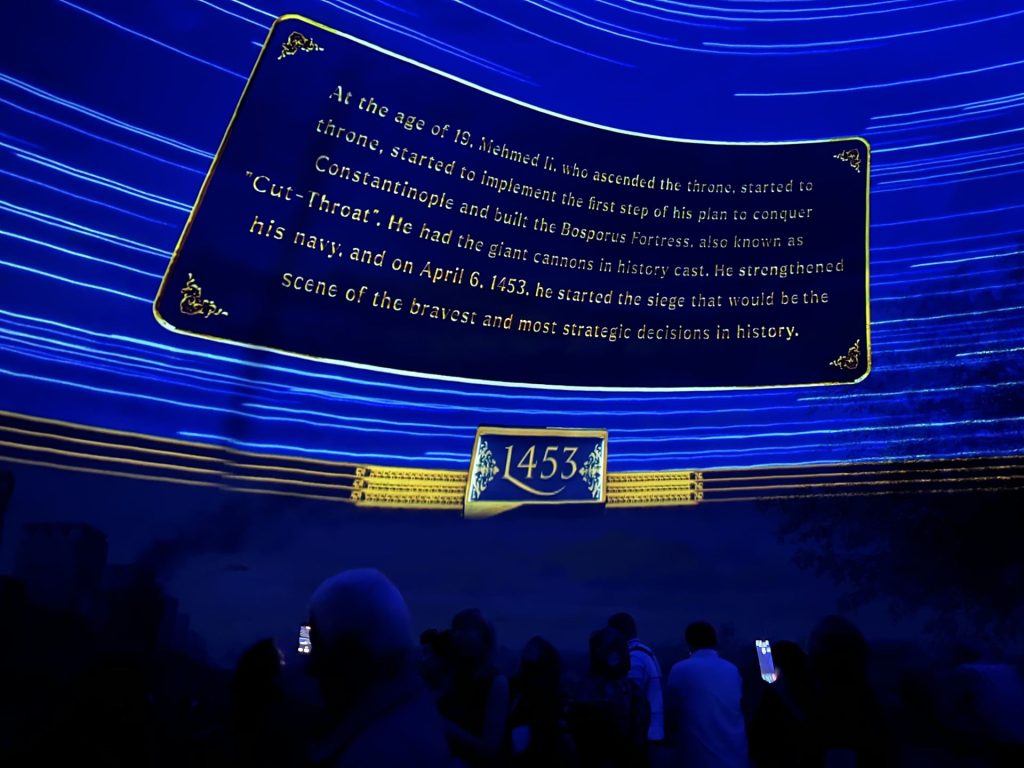

”The show you are about to watch tells how Mehmed the Conqueror, whose genius, courage and master of military tactics earned him the title of ‘World Conqueror’, realised his dreams and became the Sultan of Conquerors.”

In the newly built museum Panorama 1453 on the outskirts of Istanbul, a film screening is about to begin. A megaphone voice announces what the audience is about to see: Sultan Mehmed the Second’s cunning conquest of Constantinople, which was to be the beginning of the city as the center of the Ottoman Empire.

The museum is officially called the Panorama 1453 Historical Museum and purports to showcase historically accurate information. However, the film is more like a fantasy game. Mehmed the Second mounts a horse in front of a huge fireball, swords rain from the sky that goes from blue to red to green, cannons assemble themselves like transformers getting ready to fire at the Byzantine walls.

Behind Panorama 1453 is the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism (KTB), with direct support from President Erdogan, who has just been elected president for a new five-year term after winning the second, decisive election round.

During the 20 years of Erdogan’s leadership of the country, and especially through the last ten, a culture war has been waged. The president has used culture to glorify the country’s Ottoman legacy as a way to cling to power, whilst his political and cultural opponents have been censored, imprisoned or demonized. And throughout the recent re-election campaign, his nationalistic rhetoric intensified.

“Sacrificed on the altar of political expediency”

Upon Mehmed the Second’s conquest of Constantinople, the sultan turned the then-900-year-old Hagia Sophia from an orthodox church into a mosque. For 400 years it continued as such, until 1935, when it was changed into a museum after a decree signed by the pater patriae of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. In 2020 – almost a century later – Erdogan made it a mosque again.

In the Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association, Turkish historian Edhem Eldem argues that the conversion of the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque was not made out of genuine concern for the faithful’s need for a house of worship, but out of political populism.

“One must unfortunately come to terms with the idea that the Hagia Sophia, a target and symbol of political calculations for the past century, has been finally sacrificed on the altar of political expediency,” Eldem writes.

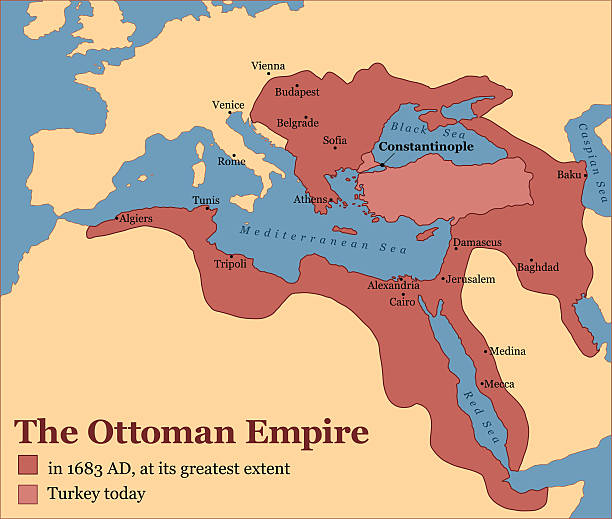

He has called the ideology behind Erdogans and his party AKP’s cultural policy a “reinvention of an imagined golden age” – a cultural policy nostalgic for a time when the Ottoman Empire stretched across North Africa, around the Red Sea to the Caspian Sea.

Embedded in this nostalgic vision is a paranoia described by political scientists as the ‘Sèvres Syndrome’ – after the Treaty of Sèvres – where the Ottoman Empire after the First World War was planned to be divided amongst the Allied Powers. This mindset implies that external (mainly the West) or internal (mainly the country’s minorities) forces are eroding the Turkish state.

Vilifying sexual minorities

“LGBT cannot infiltrate us. We will be reborn. The family is sacred,” Erdogan said in his victory speech after the final rounds of elections on May 28.

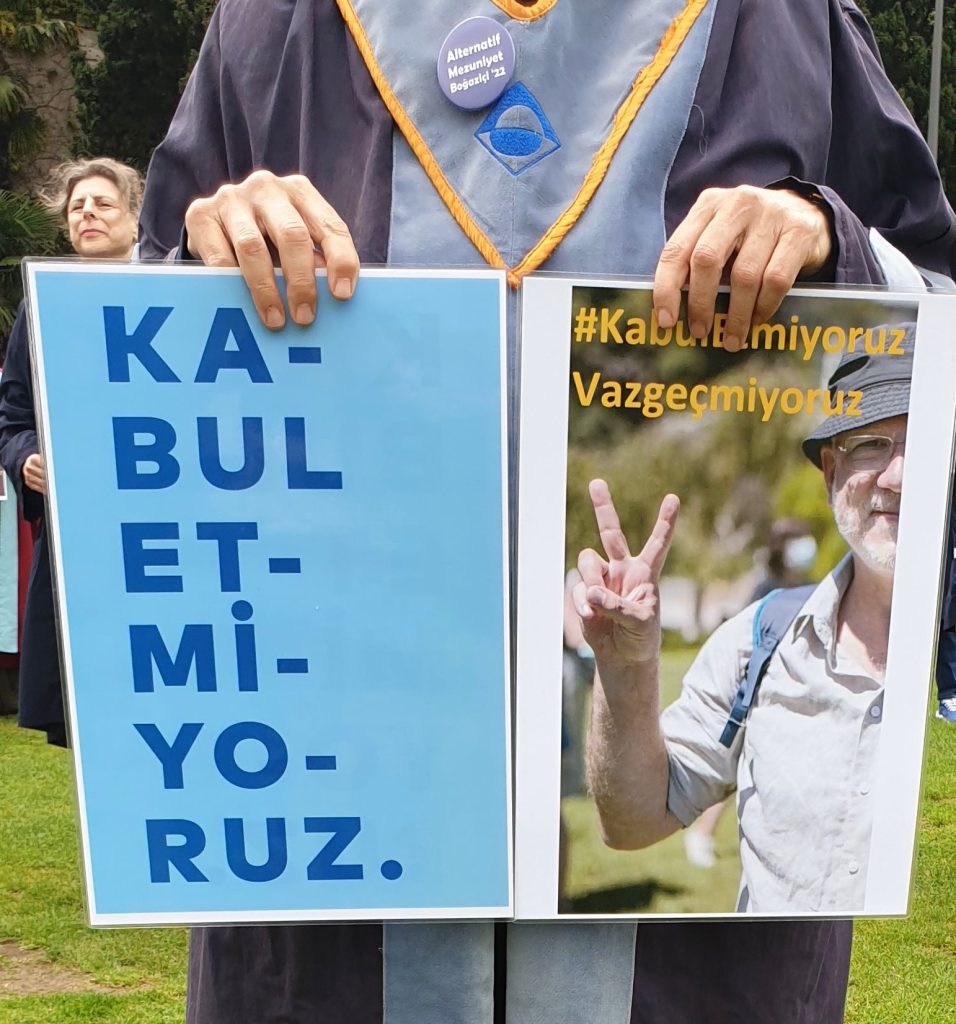

Two days later, 20 students gather outside the Istanbul Justice Palace, the city’s main courthouse. Last summer they participated in a pride parade inside their Bosphorus University campus that was stormed by police, and now they are facing charges for participating in an “unannounced gathering”. Outside the courthouse are hundreds of riot-ready police with shields and automatic rifles. A couple of plain-clothed police officers tell the students not to leave the trial as a group, and that they are not allowed to speak to media.

“The civil police are always there when we gather from the LGBTQ community,” says Mert Gunes, one of the prosecuted students. “If they decide to attack, the other police will follow.”

When the pride parade was attacked last year, a police officer hit him so hard he could not move his arm for three weeks. And to one of his friends who was lying on the ground, the police shouted “we will kill you”.

“In a democracy, the trial should be about the violation of their freedom of expression and assembly. But in a Kafkaesque way, the trial is about the students participating in a pride parade,” says Can Candan, documentary filmmaker and the students’ teacher at Bosphorus University.

He has been dismissed and reinstated (through legal appeal) twice from his professors’ position since a new rector – previously completely unknown in Turkish academia – was appointed to the university by a decree signed by the president in January 2021.

In February 2021 the university’s LGBTQ+ student club – for which Can Candan was the faculty advisor – was closed down. As a reaction of the repression by the school’s management against its queer students, the student cinema club planned an outdoor screening on campus of queer-themed films. But also this was cancelled by the new administration.

“The school management cooperates with the government to erase all existence of LGBTQ+ on campus, by using police force, by censoring and by initiating legal processes against them,” says Can Candan.

Challenging the official narrative

‘Hrant Dink was murdered here 19 January 2007’ reads an engraved paving stone on a busy street in central Istanbul. In a building a few meters from the sign is the 23.5 Hrant Dink Site of Memory, a memorial site (they do not have the rights to call themselves a museum) for Hrant Dink, journalist and founder of the Armenian newspaper Agos. The site is situated in the former editorial offices of the newspaper. Leaving work, Hrant Dink was shot dead just outside his office by a 17-year old Turkish ultra-nationalist.

Not long after the assassination, pictures surfaced with smiling police officers posing with the young killer in front of a Turkish flag. During trials, a former head of the Turkish secret service testified that the murder had “deliberately not been prevented” and that state authorities were responsible.

During his lifetime, Hrant Dink was charged three times under Article 301, according to which it is illegal to insult the Turkish nation, its institutions and its heroes. He became known to the public after criticizing Turkey’s denial of the Armenian genocide, and after he revealed that Atatürk’s adopted daughter Gökcen’s biological parents were murdered in it.

Today, the memorial site works to pass on Hrant Dink’s deed and legacy, advocating for minority rights and equal citizenship.

Following the failed military coup against Erdogan in 2016, the nation’s minority groups have suffered, as Erdogan has amplified his nationalist, anti-minority rhetoric to justify and consolidate his hold on power. Escalating during this election cycle, the level of nationalistic rhetoric has intensified from both the governing party and the opposition, leading to increased support for ultra-nationalist parties.

At the memorial site exhibitions, visitors can watch videos of Hrant Dink passionately advocating for his right to historiography and expression, as well as trying to defend himself from the persecution he endured. His words resonate like the voice of a journalist in present-day Turkey, as the country is plummeting on Reporters without borders press freedom index. Most recently, there has been waves of arrests and imprisonment of Kurdish journalists.

And it’s not just journalists who face censorship. Müstehak, a cultural magazine, published an annual report that documented various forms of repression and censorship within Turkey’s cultural sector. Last year’s report, which no longer can be retrieved from the Internet as the publications website has been forced shut down, comprised 400 pages.

“They threatened our artists who think differently”

In a majestic turn-of-the-century building on Istiklal Avenue, Istanbullus or others can now visit the newly built museum of Akif Ersoy, author of Turkey’s national anthem,

curated by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism – the same organization behind the Panorama 1453.

For the interested, the same building also hosts a much older art institution – Gallery Nev, in fact, Istanbul’s oldest gallery.

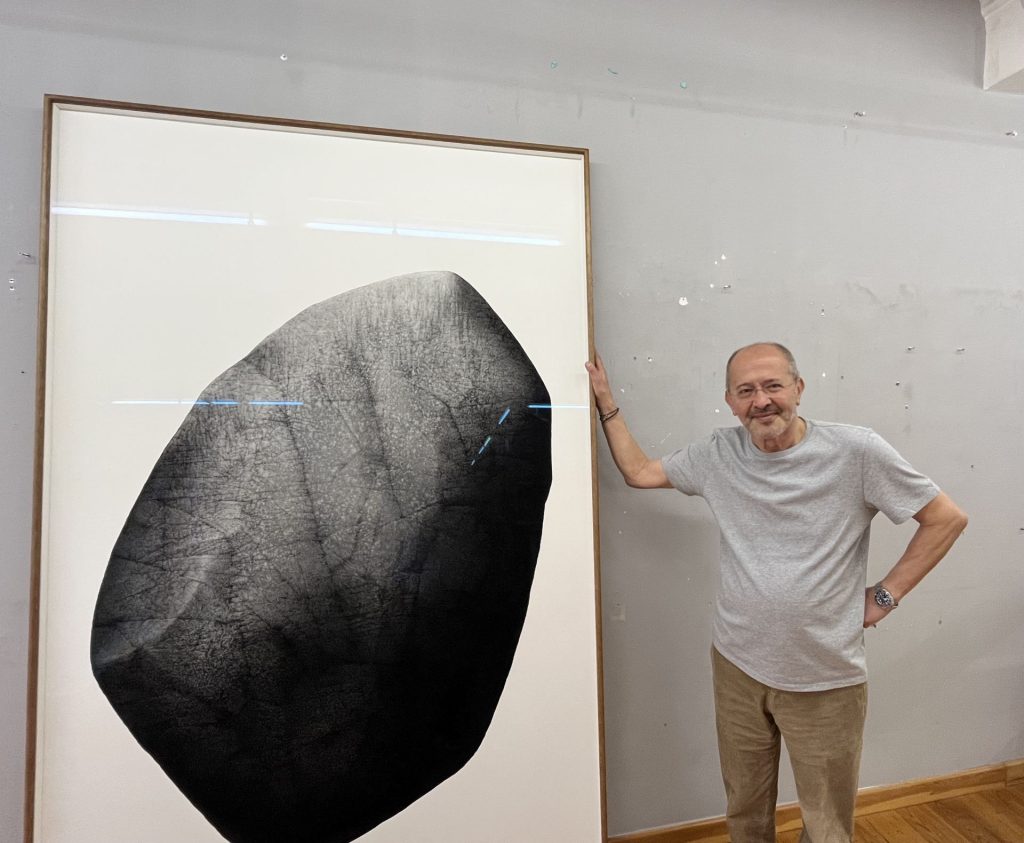

“We became the oldest two years ago, when the two older galleries close down,” says Haldun Dostoglu, owner of gallery Nev.

“When I opened my gallery in the 80s, there wasn’t much of an art scene in Istanbul. But it grew, the Istanbul Biennale became bigger and in 2004 three museums of modern art opened. Between 2000-2015, Istanbul’s art scene was very international and popular. Until the Gezi protests, then everything began to change,” Dostoglu says.

The Gezi Park protests of 2013 sought to stop the state’s plans to turn one of Istanbul’s central parks into a shopping mall, but grew into a national movement of discontent with Erdogan and the AKP. As the state used excessive police violence to quell the protests, relations between the EU and Turkey deteriorated.

Several cultural figures were prosecuted after the Gezi Park protests. One of them was Osman Kavala, philanthropist and founder of Anadolu Kültür, a non-profit organization working to create spaces for highlighting the artistic and cultural heritage of ethnic and religious minority groups. Prosecuted in a high-profile case, he is now serving a life sentence – a sentence the European Court of Justice has ruled illegal. Before that sentence, he was initially acquitted.

“We were waiting for him to be released from prison. We were so happy, hugged and laughed. One hour passed, two hours,” says Hale Tenger, an artist represented by Galleri Nev and friend of Kavala, who participated at the trial.

“And then we found out that he was imprisoned again. That is torture. Psychological torture,” she says.

Tenger herself has been subjected to legal proceedings for her art. In 1992, she was prosecuted after exhibiting a work at the Istanbul Biennale in which a work with figurines of three little monkeys formed stars and a crescent moon. She was freed of charges and took another risk with a work of the same name in 2013, just before the Gezi Park protests. That time, the piece was an illuminated labyrinth of photographs showing political and state violence, against protesters and against minorities in Turkey.

“But then nothing happened,” Tenger says. “That’s how they work. Tactically and methodically in a way so that you never know what will happen.”

Despite these intimidation methods of arbitrary arrests and persecution, there are still ways for the country’s artist guild to comment on the political situation – after years of repression, the country’s artist guild has inculcated a tradition of resistance, finding ways to express themselves with the help of irony or euphemisms. Still, a new, younger generation are often more explicit, acting without fear. And should they listen to the words of the president, there is no need for them to worry.

In his inauguration speech at the newly reopened Istanbul Modern, Erdogan said: “They threatened our artists who think differently, they tried to intimidate these people by creating a climate of fear and by putting pressure on them (…) But we overcame these difficulties. We took giant steps in culture and art”.

He then went on to comment that during the last century, Turkish art culture had failed to reconnect with the Ottoman tradition, but that now was the time for a “mental revolution”.

An imperial dream

In the cinema hall at Panorama 1453, the megaphone voice subsides and as visitors begin to leave the theater, some linger to see the still images that are now projected against the film dome: lined up soldiers with Ottoman flags and a burnt olive tree.

For many, the imperial dream the museum is conveying – Erdogan’s “mental revolution” – represents an existential threat.

“I’m fearful. Frightened,” said Gunes after the trial against him and his classmates. “For five more years we will have to live under the rule of the AKP. As anti-LGBTQ discourse will increase, police will attack us even more”.